The nonprofit magazine Behavioral Scientist hosted three free writing workshops in May and June 2022. Although the goal was to help researchers better communicate their behavioral science findings, the neuroscience-based tips were helpful for anyone who wants to write more clearly and concisely. I really enjoyed all three 60-minute sessions, so I wanted to share my notes and support the great work of Evan Nesterak and the rest of the Behavioral Scientist team.

The sessions were led by members of the Behavioral Scientist editorial team and featured guest scientists and authors from the scientific community who shared their experiences and advice. More than 1,350 people from 72 countries registered for the workshops – I was lucky enough to be one of them, and these were my key takeaways from the sessions:

Session 1

Clarity and cohesion with behavioral scientist and writer Cameron French

In this session, Cameron discussed the three strategies that make writing clear and coherent, and explained each of them using scientific writing as an example.

Strategy 1 – What makes a sentence clear

If the subject is too far from the main verb, the sentence becomes confusing to understand, as in the following example (all the examples in this post are from the slide deck):

To avoid this:

- Start sentences with short subjects and a verb.

- Always structure sentences so that the subjects are close to the verb – a helpful rule is that the verb cannot be more than seven words away from the subject.

Strategy 2 – What makes writing flowy

A fluent and enjoyable text begins with information that is familiar to the reader and then presents new and/or complex information at the end of the sentence or paragraph. This works because:

1 – It starts by drawing the reader into the content. (“This is easy to read, I understand this!”)

2 – Existing schemas are activated as the reader connects what they just read to something they already know. (“Oh, I know something about that!“)

3 – Pulls the reader along between sentences (“I see how this new thing fits in with what I’ve already read!“)

So, start with information readers are familiar with and end with information they cannot anticipate.

Another tip for better flow: When referring to something in a previous sentence with words like this, these, that, those, another, such, second or more, put the word at the beginning of the sentence or near it.

Strategy 3 – What makes writing lively and animated

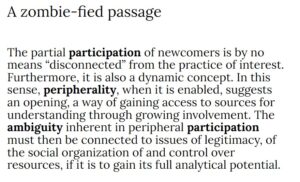

Some writing is lively and animated while others are dull and boring. This is usually because boring texts use nominalization (aka zombie nouns), which is when we put the action in the noun instead of the verb – usually with words ending in “tion” and “ent”

Here’s are two opposite examples:

The difference is clear, so always slay zombie nouns and put the action in the verbs.

These are some zombie nouns you should avoid:

Q&A with Leidy Klotz, author of “Subtract – The Untapped science of less”

Leidy spoke briefly about his book – which I’ve added to my reading list – and offered the following advice:

- Communication is about conveying knowledge in a way that’s understandable. To make the content easier for readers to digest, get feedback from others, especially people in your target audience, and revise the way you present the information based on that feedback.

- Follow Stephen King’s advice to “kill your darlings”: it’s hard, but important, to consciously edit out some of what you’ve written to make your content easier to read. If you can’t do it yourself, have someone else cut out the words for you.

- Save the passages you cut out, such as stories and strong sentences, in a separate document to use in future writing.

- The writing process usually involves three types of writing:

1. Free flow – Sit down and write whatever comes to mind.

2. Non writing – Take time to think and figure out the structure of the story, giving the ideas time and space to develop.

3. Time in between revisions – Let the draft sit for some time and then edit it again, iterating.

Session 2

Aligning ideas with outlets, with Evan Nesterak + pitching tips from Dave Nussbaum, founder of Psychgeist Media

This session was about how to contact the media to get your writing published – least helpful to me because I worked in PR for many years, but interesting nonetheless.

Evan opened the session by noting that we often start writing in isolation from what’s going on around us and then try to find a place to publish what we’ve written. It’s more productive to understand where we want to be published and then write according to the style, audience, and goal of the publication.

Questions to consider when aligning your project with an outlet

1. What’s the goal of your article?

- Who are you trying to reach? Why are you trying to reach them?

- What value will you deliver to these people? Why is it important?

Always answer these questions before you write so you know how to write, where to write to, and how to reach the right audience.

2. Who are your target audiences?

Every outlet has a target audience, a set of article formats it accepts, and target contributors. Read the submission guidelines and previous articles to find out if you’re a good fit and how to create the content.

3. What are your parameters?

Match your goals and content with the parameters of the outlet, e.g. word count, writing style, etc.

Types of outlets to consider: National/international, general/topic, professional, corporate/ personal blog

- The largest or most popular outlet isn’t always the best for your goals and content.

Session 3

Memorable Hooks & Meaningful Intros with Cameron French

To start an article well, you need to craft a strong introduction to hook the reader so the rest of the text flows smoothly. Cameron’s tips were once again excellent!

A strong introduction must prepare readers in two ways:

1 – Let them know what to expect so they can read more knowledgeably.

2 – Motivate readers so they want to read more closely.

Most good introductions consist of the following three parts:

1. Shared context

A shared context activates existing schemas – patterns of thinking that organize information and the relationships between them.

Readers are more likely to judge a text as clear if it begins with a short section that they can easily understand. This sets the stage for the longer and more complex section that follows.

2. Problem

The problem can be divided into two aspects:

The condition (what the problem is) + the consequence of the problem (what happens if we don’t solve the problem – making this clear gets people to read on)

Strategy for framing the problem: Make it intriguing, surprising, unconventional to get people’s curiosity and attention.

“What makes an idea interesting is when it departs from conventional wisdom. If somebody just affirms your assumptions, you don’t get curious, you don’t get intrigued, there’s no surprise.”

Adam Grant

You can hint at the surprise, the intrigue, in the introduction, even if you don’t want to reveal it until the end of the text.

– Even if you aren’t talking about a consequence of the problem, but about an option, you must show why the thing you’re writing about is important to the reader. Your job as a writer is to transfer your problem to the reader.

– Always emphasize why the reader should keep reading

3. Solution / Claim

Three ways to end a sentence with a climax (special emphasis):

1. Weighty words

Cut out zombie nouns and use remarkable words, good sounding words, worthy words, rhythmic words, as in the following example:

2. Of + weighty word

“Of” followed by a weighty word makes the sentence more dramatic. For example:

“The rescue and liberation of the old”

“races condemned to one hundred year of solitude”

3. Echoes

Repeat words or arrange them to create interesting, attention-grabbing sounds:

Q&A with Elizabeth Weingarten, head of behavioral science insights at Torch and senior advisor at Behavioral Scientist

Journalists are trained to find strong and compelling narratives. How can you do that for science or whatever you write about?

There are several components to consider when it comes to narratives and storytelling:

1 – Narratives have a beginning, middle, and end – It’s much easier to read and understand content that follows this structure.

2 – Narratives also have protagonists, a setting, and a resolution – You can’t always use all of these elements in every piece of content you create, but it’s important to be creative with the details and elements you put into the story, even when describing research. For example, is there a character that can make the story come alive? A researcher, you, someone you’ve talked to…

3- Facts and ideas are stickier and more understandable when they follow a narrative. – When writing about a scientific study, take a step back and think about how you can fit it into the larger context or narrative to make it interesting.

“What’s the narrative here and how can I talk about it?” Think creatively about how you can talk about your topic and make it more interesting – details and stories during the research, the context in which it took place… seemingly unrelated things that make your topic more interesting and engaging.

Need to report on a project? Elizabeth gave tips to make it easier:

– Prepare from the beginning. Take 30 minutes to brainstorm the points you want to talk about and how you’ll prepare to write about them (list the people you’ll interview, ask permission to use their quotes in the future, etc.).

– Keep a journal of your research process – stories, interesting things you noticed, questions that were raised. They’ll inspire you to write later.

– Try to publish the project even before you finish it. This is also a good way to get feedback from others (it reminded me of Austin Kleon’s concept of learning in public, where you share your progress with others).

– Sit down and write whenever you feel like sharing, even if you don’t think your project is ready yet. Write and see what comes out. This way you’ll avoid procrastination and know if you’re really ready to share or not.

– We can learn as much about behavioral science – human behavior, passions, triggers, emotions – from novelists as we can from science writers, so it’s important to read novels, too.

– Find an article, book, or other writing material you like, and then evaluate what’s so good about it (style, details, storytelling, etc.), and then apply it to your writing. (This reminded me once again of Austin Kleon’s advice, this time from Steal Like an Artist).

Watch the workshop

All sessions and slide decks are available for free at Behavioral Scientist Writing Workshop Spring/Summer 2022. And subscribe to Behavioral Science’s weekly newsletter if you want to learn more – it’s really cool!